The 1972 Egyptian classic enjoys a gorgeous, brand new restoration, allowing younger audiences to discover its magic and its message, while bestowing on those revisiting the film an eerie sense of “what could have been?”

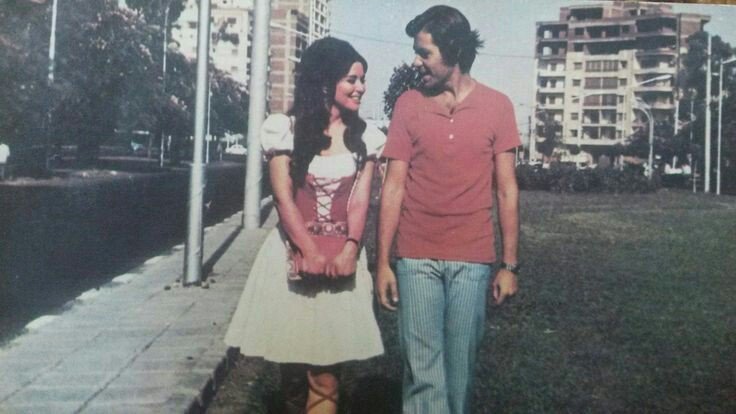

Watching the 1972 classic Watch Out for Zouzou (‘Khally ballak men ZouZou’), filmed in Cairo and featuring some of the most beloved Egyptian stars of the time, one feels like the country’s capital could easily be mistaken for any metropolis of the era, throughout Europe and even the Americas. Yet, if we fast forward fifty years — the film was restored to celebrate half a century since it was premiered — what we find is a world divided, and in Cairo, a chaotic city overrun with traffic, alongside an eerie sense of what could have been. Gone are the Seventies outfits, of course out of date today, the free love tropes and the carefree songs, replaced instead by a society that, at least as it appears in the contemporary movies coming out of Egypt, is puritanical, alienated from the rest of the world and closed off.

Yet when I watched the film, brought back to its splendor by a collaboration between the Red Sea Film Festival Foundation along with the Egyptian Ministry of Culture, Arab Radio and Television Network (ART), and the Media Production City in Egypt, which aim to restore and screen classic Egyptian films, I couldn’t help but feel this could easily be a Bollywood film from the same time, or even an Eduardo De Filippo Neapolitan melodrama for Italian TV. There is a little of Totò too, our beloved Italian comedian, who was nicknamed ‘the prince of laughter’.

Apart from the different language, in Zouzou’s case Arabic, the Egyptian classic is really a story about the times, the 70’s and the youths trying to own it, as well as the class divide that has always ruled, in one shape, way or form, all societies, since the beginning of time.

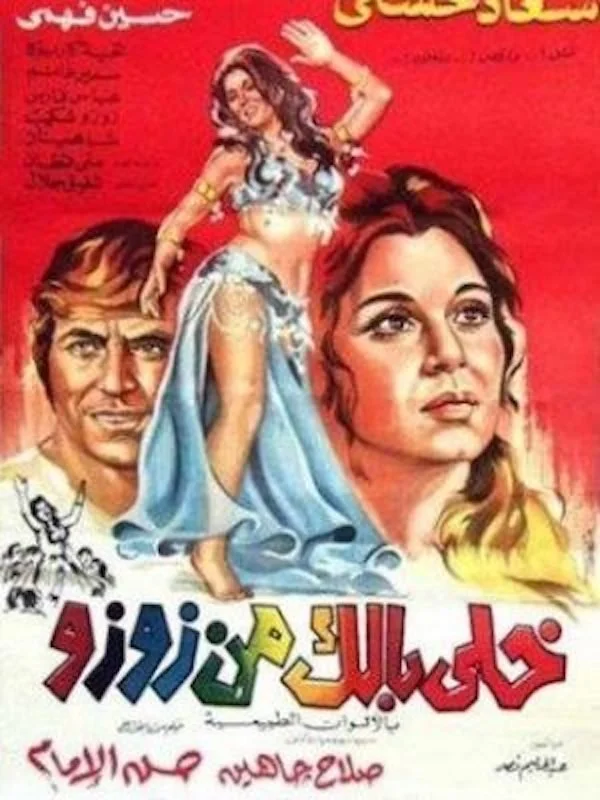

Watch Out for Zouzou first premiered in November of 1972, inside the Cairo Opera House and it quickly became such a success that it continued its run in cinemas for a record number of weeks, becoming one of the highest-grossing Egyptian films of all time. Families remember taking out the VHS tape every holiday to watch it together and it also aired on national TV in Egypt from time to time. The film stars the phenomenal Soad Hosny – known affectionately as the ‘Cinderella of the Screen’ and who died a mysterious death in London in the early 2000’s — as Zouzou, a student at university who hails from Cairo’s Mohammed Ali Street, the area renowned as a dancers’ and musicians’ colony. But Zouzou wishes to keep her profession as a belly dancer, with her mom’s troupe performing at weddings, a secret. Because Mohammed Ali Street is not just an address, it’s a social standing, and one that doesn’t allow Zouzou for much growing and bettering herself. The similarities here with the beloved Neapolitan-born Totò, for the proud daughter of a Parthenopean mom, are multiple. He too was born into poverty, in the characteristic Rione Sanità, which features dwellings called “bassi” — short for “bassifondi” or basements — and rose to nobility later in life, discovering he was the illegitimate son of a nobleman.

But back to our story, in Cairo. So into the mix of Zouzou’s life, in comes Hussein Fahmy — for yours truly an extra layer of delicious viewing as I’ve had many a face to face with the star who is now the President of the Cairo International Film Festival — as Professor Said Kamel, a handsome, young, drama teacher at the university. As Said’s and Zouzou’s paths collide, quite literally, the story heats up. And the soap opera behind the scenes, involving a soon-to-be ex fiancé, mothers, fathers and other students, and of course, the class difference between the two lovers, begins to bring things to a boil.

But while reading these words may make you want to dismiss the film as just another cinematic fluff piece, Watch Out for Zouzou instead proves a testimonial to a time gone by, as well as holding up a mirror to a society that could have been. Filmmakers are often prophets, because what they make, the films they shoot, must survive the test of time, and while Zouzou’s clothes can be a bit over the top for today’s world, the message of the film bearing her name in the title is very well grounded in reality. Or rather, a reality that was and could still be, without the issues now faced by the Arab world. One must remember that Zouzou came out in the aftermath of the 1967 Arab-Israeli War, which transformed the Region, created unlikely alliances and left lasting effects in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict along with regional tensions.

There is a reason why Egyptian films were the most watched and beloved cinema throughout the Arab world and the diaspora living abroad. Everyone can understand, even yours truly at times, the Arabic spoken so crisply by the actors, and the stories have a universality that goes beyond the cute faces and silly jokes. There is also a reason why, as of the Arab Spring, cinema from Egypt has been under attack and one of the first industries to fall victim to the new world order was film making. Not Ramadan series, which prove A-OK with the more fundamentalists voices introduced into the country by the Saudis, but films, which possessed a freedom all their own, as Zouzou proves beyond a doubt.

Hosny’s dark haired, brown-eyed great looks are only rivaled by Fahmy’s blue eyed and caramel colored complexion, his kind voice and the way he walks — never taking himself too seriously. Both actors, and the great team of supporting players, which include Zouzou’s mom (another legend, Taheyya Kariokka) and Mohiy Ismail, who portrays Omran, the fundamentalist student whose life is changed by Zouzou’s ways, form a divine ensemble of cinematic magic.

At one point, one of the characters utters the following words, and I paraphrase a bit: “We Egyptians are unsure if we hate ourselves or the world,” which can become a mantra, one in deep need of breaking, for a specific section of society from and in the Arab world today. Increasingly, I feel more and more hostility when I come in contact with some section of the Arab diaspora intelligentsia, not the everyday folks but those holding a degree, or worse. It feels like a kind of passive aggressive questioning of why I would ever be interested in their culture, their cinema, their countries — which to me is so clearly understood! Some are quick to pounce on any word I use in my headlines which they find problematic (something like “controversial” which, of course, is used in media all the time) while others think my writing is sentimental and I’m an orientalist, and have told me in so many words. I keep reminding myself that our histories, as Arabs and non-Arabs, have been problematic and I need to tread softly when approaching any culture that is not my own these days. The higher powers, those that aim to separate us and make us all stick to our ever-increasingly smaller boxes of belonging, are succeeding in their very devious plans and are often sheep masqueraded in liberal’s clothing. But speaking truthfully and carrying a big white flag should always prove my intentions and I hope that this “Us vs. Them” mentality soon goes away, because particularly for some of us, our paths and histories have been parallel, tied and very similar.

As a final word, there is also a slap in the film, as Said hits Zouzou in an effort to make her see the light, and the power of his love. It is a moment which of course would be unthinkable today, but which acts as a sort of wake up call in the film, for the audience too, as the length of the film begins wearing on us. It is perhaps the only note which dates the film, but many women living in Egypt’s highly patriarchal society would disagree, I’m sure. So perhaps, just as the songs in the film are so catchy they have become part of my humming since watching Zouzou at the opening of SAFAR two nights ago, this note too strikes a chord, dissonant as it may be, which still rings true today.

You can still catch Watch Out for Zouzou in cinemas around the UK, as SAFAR comes to a city near you until June 28th. Check out the festival’s full program here.