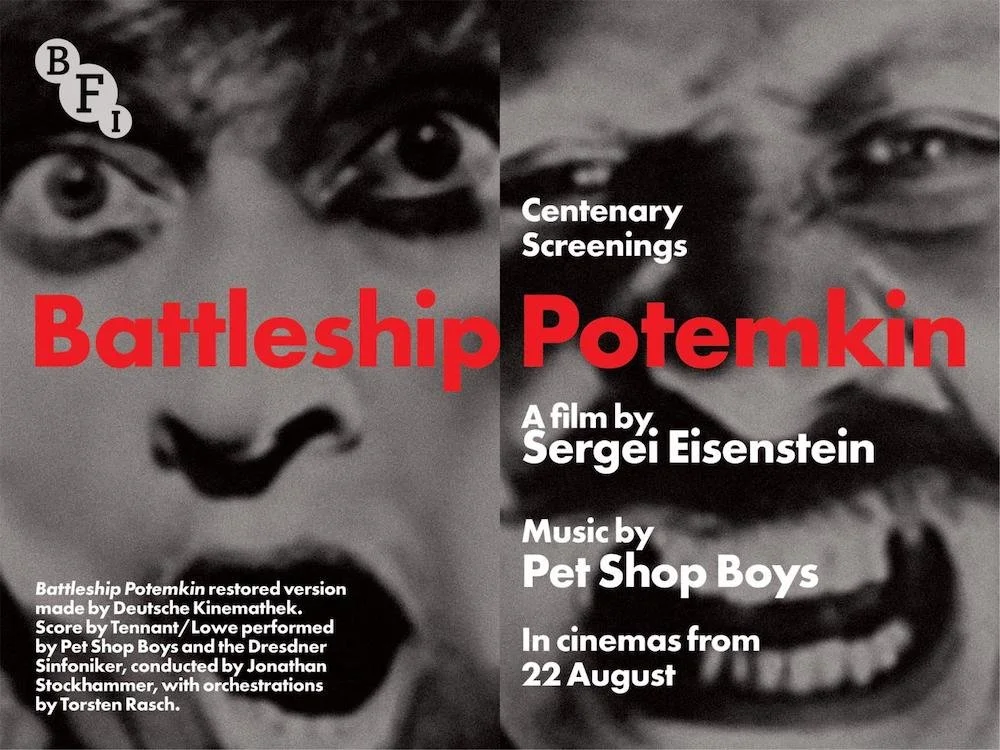

The iconic film has never looked so good or sounded so hauntingly modern and this remastered version, courtesy of the Deutsche Kinemathek, will be in UK cinemas starting August 22nd. Why watch it, you may ask? Because the 1925 film has never been so bang on, filled with actuality and gravitas.

How can a silent, black and white film made before sound even came into the Seventh Art hit at a viewer’s heart so deeply and devastatingly? If the film is Russian (Latvian actually) filmmaker Sergei Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin, it is because the story talks of issues that we are still grappling with today. Could the army — or members of the Navy in this case — be swayed to help out a proletarian cause, as was the case with the mutiny of Russian sailors against their tyrannical superiors aboard the battleship Potemkin during the Revolution of 1905?

We certainly would welcome that in a certain country in the middle of the Middle East which is ruled by a tyrannical leader who seems hell bent on creating a WWIII to appease his own trauma. But I’m digressing, and I don’t wish to take anything away from this masterpiece of a film.

Battleship Potemkin is barely over an hour long, 75 minutes in actuality, and stars actors we know little about. No big stars, no CGI special effects, just a languid, yet meticulously put together series of images that grab our attention from the first shot and never let go, until the end credits. Along with this new score by Neil Tennant of The Pet Shop Boys, the film pushes itself into the deepest recesses of one’s heart and soul, never to leave again.

Told in five acts, starting with Act I: Men and Maggots; followed by Act II: Drama on the Deck; then Act III: Appeal from the Dead; then the iconic, often imitated but never replicated Act IV: The Odessa Steps; and ending with Act V: One Against All, the film has become one of the undisputed great masterpieces of world cinema.

On 22 August 2025, Battleship Potemkin with music by Pet Shop Boys will open in selected cinemas in the UK and Ireland. Ahead of a week-long run, a special double screening event at BFI Southbank on Friday 5 September 2025 at 6.30pm, will begin with Pet Shop Boys’ feature film It Couldn’t Happen Here (1988), in memory of its late director, Jack Bond, followed by a Q&A with Neil Tennant, hosted by Paul Tickell, and then a screening of Battleship Potemkin. That screening, alas, is already sold out and why wouldn’t it be!

Battleship Potemkin was banned in quite a few countries soon after being released in 1925, due to what many censor boards perceived as its “subversive nature.” Beating the censors, finally, the film was rereleased initially in 2005, with a special screening at the Berlin Film Festival, featuring the score composed by Edmund Meisel, which was commissioned after the Moscow release of the film by the director himself, Eisenstein. As a lesser known fact, The Pet Shop Boys’ score, along with extracts from Shostokovich symphonies, were tagged onto the film to fill in the missing score by the Austrian-born composer. But the Berlinale screening finally gave the film its due glamour, along with the rediscovered score by Meisel which was composed under Eisenstein’s close supervision, and audiences were unsurprisingly spellbound.

Even today, watching the Odessa Steps, the haunting sequence of the revolutionaries meeting the Cossacks soldiers, to tragic consequences for the former, proves an out-of-body experience. My mind kept switching back to Brian De Palma’s nod to Eisenstein in his 1987 film The Untouchables, which pays homage to the 1925 classic through the use of the staircase in Chicago’s Union Station, complete with descending baby carriage and a stillness all around that gave one chills. But watching the original, on the big screen, with the close ups of faces — first celebrating their revolutionary victory, then distorted in horror and pain — was something else altogether. And maybe the poignancy of Odessa being part of Russia then, while today in the midst of the conflict as part of Ukraine, also added an extra punch.

Whatever it was, even as I write this, I still shiver when I think of it. The density of Eisenstein’s filmmaking, packing his 75-minute film with 1,346 shots, whereas the average film made in 1925/26 ran 90 minutes and had around 600 shots, makes for a “modern” viewing, not the accelerated, often ridiculous-looking speed of his contemporaries.

Another very contemporary aspect of Eisenstein’s filmmaking is his homoerotic viewpoint. Sailors lounging in their hammocks on the ship, shirtless, men hugging passionately at victory, the contorted faces of the victims of the Odessa Steps massacre, it’s all very current and modern, even if it’s shot in black and white. Actually, the denseness of the medium, the hues of the film seem to bring out a Robert Mapplethorpe-like eroticism, which adds an extra layer of magic for this lover of the late NYC photographer, along with the soundtrack of The Pet Shop Boys. I mean, isn’t all written by the duo a gay anthem of sorts, and thank goodness for that!

If you still need a reason to go, here is a quick recap of the story of Battleship Potemkin for you. In June of 1905 members of the crew of the Potemkin, an Imperial Russian battleship, refuse to eat the maggot-infested meat they are served in their borscht. Their superiors judge them in insubordination and those crew members are rounded up, covered with a sheet and prepared to be shot, by the remaining crew members of the Potemkin. But this doesn’t go according to plan, and the sailors overwhelm the outnumbered officers and take control of the ship. However, one man Vakulinchuk, the charismatic leader of the rebels, is killed. His body is laid out in the port for all to pay their respects and an anthem is born out of his martyr-hood: "For a spoonful of borscht.” The citizens of Odessa, then part of Russia, take to their boats, sailing out to the Potemkin to support the sailors, while more crowds gather on the Odessa steps to cheer on the rebels. In come the Cossacks and the rest, as they say, is history. Or rather, you will have to watch at the movies.

To view the film on the big screen, and I urge you to do so as it’s way too large a spectacle for a mini screen or your TV even, you can find tickets and more info on the BFI website.

Images courtesy of the BFI, used with permission.